While I was at the Insights Association South East Chapter’s Annual Spring Event in New Orleans, I was fortunate to have an opportunity to present a seminar of my own. It was a fantastic event, packed full of learning on a diverse variety of topics – from blockchain to storytelling, consumer insight trends and data fluency.

You can read a write up of the full event here, and my summary of the panel session here. But in this piece, I wanted to provide an overview of the topic I spoke on and the key points that we covered. The topic I explored was how to apply journalistic principles to enhance the effectiveness of market research reports.

Driving Informed Decisions

My presentation opened by breaking down what exactly it means to drive informed decisions, taking into consideration the old adage of getting the right data to (and from) the right people at the right time. But really, informing decisions in today’s fast paced world is about more than that – it’s about telling the right story with that data. Because no matter how objective we try to be, as researchers, our audience will always read a narrative into the data we present. It’s human nature; an immutable fact of life.

Of course, finding the right story is tough. Not just from a practical point of view, but also because influencing the story that data tells introduces a set of ethical, moral and commercial challenges.

Fortunately, market research is not the only profession that faces these challenges. So to dissect how we can construct the right story, and what the right story even looks like, it’s worth borrowing from two organisations that have dedicated significant resources to answering this exact question – the Ethical Journalism Network and the American Press Association.

The Principles of Journalism

Below are the three key principles of journalism that I covered throughout the presentation, as well as a deeper dive into my favourite concept from this subject - what it means to be proportional in writing.

Principle 1 – Strive to be truthful and accurate.

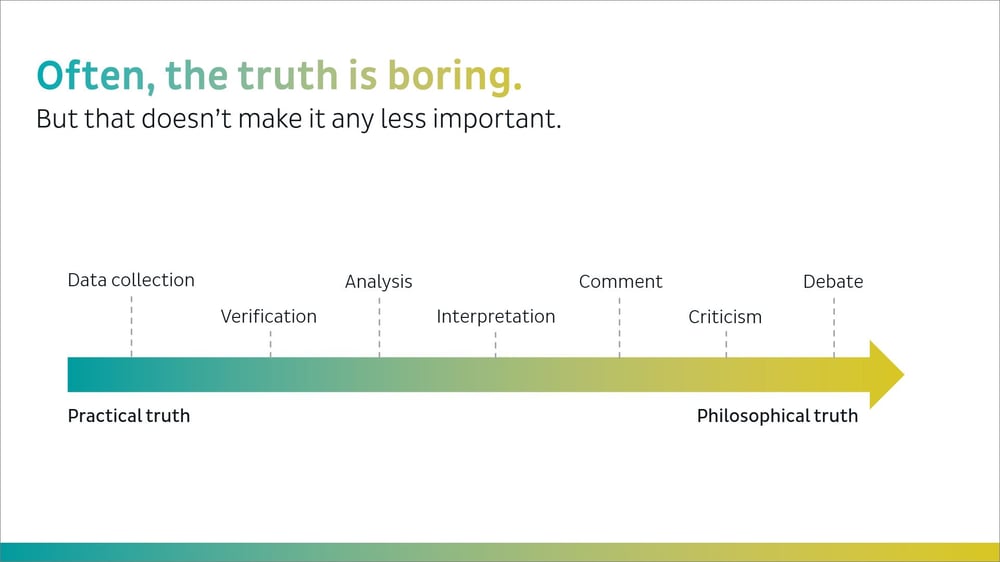

In theory it’s a simple principal, but much more challenging in practice. That’s because quite often the truth is boring. Sure, seven out of ten customers may buy from brand X again. They may have liked the price and product quality, but thought that the purchase experience could have been better. It’s true, but it’s not exciting, stimulating or engaging – and these facts don’t help decision makers make the right choices.

To make the truths we tell more interesting, it’s worth considering what I like to call the scale of truth. This isn’t a measure of how accurate something is, but rather what kind of truth it is, on a spectrum of practical to philosophical. A practical truth is something that is universally accepted, driven by data collection and analysis. As we move across the scale towards philosophical truths, we layer in more interpretation, comment, criticism and debate. These are truths that we may believe, but can be argued, challenged and debated.

| Tweet This | |

| The scale of truth plots practical and philosophical truths on a scale, moving from the universally true to the more subjective, engaging and stimulating. |

A good, engaging research report will cover the full spectrum of truth, starting with a basis of fact, and progressing to a more interpretative conversation that stimulates and engages stakeholders with philosophical truths.

Principle 2 – Be independent.

In general, journalists aim to be independent of two groups; those they cover and those they report to. In the research industry, we have a surprisingly similar setup. Our customers are those we report on, and our employees or clients are those we report to.

In order to really understand a situation, it's important that we try to remove ourselves from these two groups and find an independent voice. That may mean telling some cold, hard truths to our stakeholders in some situations, and in others, it may mean coming to terms with uncomfortable truths about our own purchasing habits.

Principle 3 – Be loyal to citizens.

Almost in contradiction to the second principle, journalists also aim to be loyal to citizens. As researchers, if we apply that principle to ourselves it means recognising that we are the main voice of the customer in any given organisation and driving that voice across business functions.

To build towards a company culture, it’s important to be data driven; encouraging decision makers to look at the available information on a subject in order to make informed choices. It’s also vital to ensure robust feedback systems are in place and that this feedback can get to the right people. If a customer compliments your product on Twitter, does this reach the product development team? Do frontline customer service staff hear about the NPS scores they directly affect? And finally, we need to be constructive as research projects often reflect negative customer opinions and frustrations that are not the most engaging for stakeholders to hear. It’s our job, and our challenge, to take this feedback and present it as an opportunity.

The Concept of Proportionality

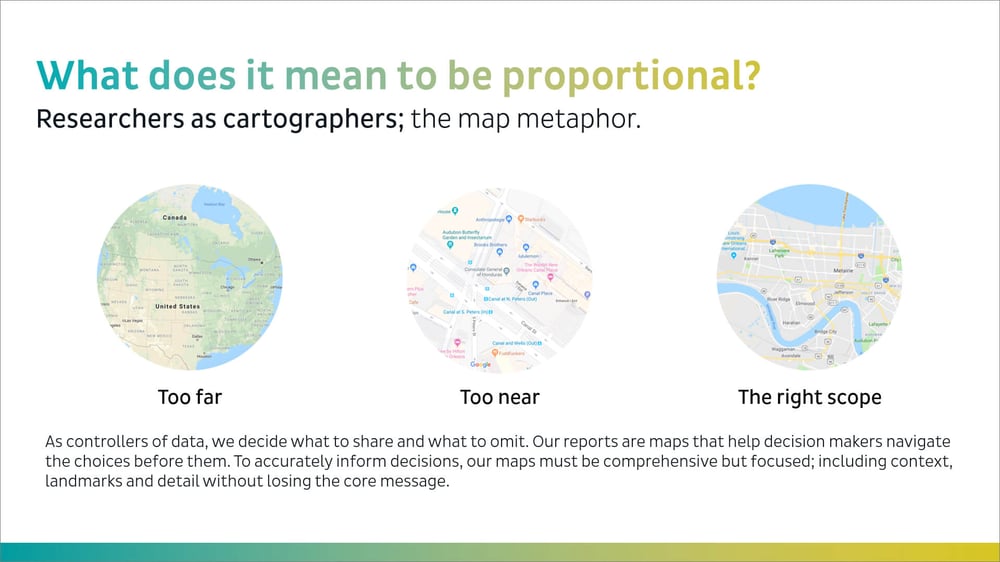

The final principle of journalism is that of proportionality. The best way to explain what it means to be proportional is with a metaphor. Think of journalists and researchers as cartographers. It's our job to draw a map.

The first decision to make is how much to draw. If we draw too much, we aren’t able to see where we start or end because there’s too much surrounding context, the directions are lost in the excess. But if we draw too little, we don’t have enough context to orient ourselves correctly.

Ultimately, as controllers of data, we decide what to share and what to omit. Our reports are maps that help decision makers navigate the choices before them. To accurately inform decisions, our maps must be comprehensive but focused; including context, landmarks and detail without losing the core message.

But a map is no good if no-one reads it. So in addition to making smart decisions about scope, researchers can also borrow literary devices from the journalistic profession in order to keep readers and stakeholders engaged. Peter Cole from The Guardian has a fantastic list of rules for writing news copy, but here are top four that are particularly applicable to market research:

- Keep it simple. Decision makers don’t have much time, so need easy to digest information.

- Give every sentence a purpose. If the sentence adds nothing, it is not necessary.

- The active tense is always faster and more immediate than the passive tense.

- Be positive even when negative. Writing is more engaging when it describes what is happening, rather than what is not.

Finally, I closed on a note about the inverted pyramid structure; a concept which states writers should aim to include the most important information first and less important information later in the piece. To highlight this, I referenced a surprising Washington Post study which found less than 50% of Americans state they regularly read more than just the headline of news articles. That means is the key points are not accessible within the first couple of words, less than 50% of all audience members will ever see it.

| Tweet This | |

| Less than 50% of Americans report regularly reading a news story in more depth than the headline. If your point isn't clear in the headline, most of your audience will never see it. |

And with that fact, I brought the presentation to a close. If there is one thing I hope people will take away from the presentation and this summary, it’s that researchers write with purpose, just like journalists. If we want to successfully affect decisions in a positive way, we should be looking to and learning from a profession that has dedicated huge volumes of resources to figuring out how to ethically and fairly write with a purpose in mind. There’s a lot we can learn from journalism both in terms of practical skills and addressing more complex philosophical challenges. If we do that, I believe the research industry as an aggregate will become hugely more efficient at driving informed decisions.